The intricate web of wires beneath your vessel's deck isn't just a jumble; it's the nervous system that brings your boat to life, powering everything from critical navigation lights to the beloved coffee maker. Understanding Navigation, Lighting, and Accessory Wiring Schematics isn't merely about troubleshooting a blown fuse; it’s about safety, reliability, and the peace of mind that comes from a well-engineered electrical system. Without these visual maps, even a seasoned sailor can find themselves lost in a maze of color-coded spaghetti.

At a Glance: Your Vessel's Electrical Compass

- Schematics are Your Guide: They provide a clear visual roadmap of your vessel's electrical system, showing how electricity flows.

- Safety First: Correct wiring is crucial for preventing fires, electrical shocks, and equipment failure.

- Troubleshooting Made Easy: Diagrams help you quickly pinpoint and fix issues like incorrect wiring, blown fuses, or corroded connections.

- Essential for Installation: Whether installing new nav lights or upgrading accessories, schematics ensure everything is hooked up correctly.

- Compliance Matters: Adhering to wiring standards is vital for meeting marine regulations and ensuring legal operation.

- Empower Your DIY: Even if you hire professionals, understanding schematics empowers you to make informed decisions and ask the right questions.

The Unsung Hero of Vessel Operations: Why Schematics Matter

Imagine navigating a busy channel at night without your navigation lights, or having your bilge pump fail during a sudden downpour. These aren't just inconveniences; they're potential disasters. This is precisely why navigation lights wiring diagrams are essential for any vessel owner, as they offer an easy-to-understand visual representation of your electrical system. This clarity helps ensure that electricity flows in the proper direction and with the right amount of power to all components, especially critical navigation lights.

Think of wiring schematics not as a dry technical drawing, but as the blueprint to your vessel's operational heart. They're invaluable for:

- Diagnosing Issues: Quickly identifying and fixing common problems, from incorrect wiring to a stubborn short circuit.

- Ensuring Proper Installation: Vital when installing new equipment, ensuring all components are hooked up correctly and safely.

- Preventive Maintenance: Spotting potential weaknesses before they become critical failures, such as corroded connections.

- Upgrades and Modifications: Planning and executing additions like new electronics or an upgraded stereo system without introducing hazards or overtaxing your existing system.

- Regulatory Compliance: Meeting safety standards set by organizations like the Coast Guard or international bodies.

In essence, a comprehensive understanding of your vessel's electrical schematics isn't just good practice; it's a fundamental aspect of responsible seamanship, crucial for safety and efficiency on the water.

Decoding the Language of Wires: Key Symbols and Components

Before you can read a schematic, you need to understand its alphabet. Schematics use standardized symbols to represent various electrical components. Think of them as shorthand, allowing complex systems to be drawn clearly and concisely.

Common Schematic Symbols You'll Encounter:

- Battery: Represents the power source, typically a rectangle with positive (+) and negative (-) terminals.

- Fuse/Circuit Breaker: A protective device. Fuses are usually a jagged line or a rectangle with a line through it; circuit breakers often look like a switch with an internal overload mechanism.

- Switch: Controls the flow of electricity. Different types exist (toggle, rocker, momentary), each with its own symbol (e.g., a simple break in a line with a pivot point).

- Light/Lamp: A circle with a cross or a loop inside, indicating a load that produces light.

- Motor/Pump: A circle with an 'M' inside.

- Resistor: A jagged line, used to limit current.

- Diode: An arrow with a line across its tip, allowing current to flow in one direction only.

- Ground: A series of decreasing parallel lines, representing the connection to the vessel's common negative return path.

- Wire: A simple line connecting components. Often colored or numbered in real-world applications, which might be indicated on the schematic itself.

The Building Blocks: Basic Electrical Components

Every electrical circuit on your boat, no matter how simple or complex, relies on a few core component types:

- Power Source: This is where the electricity originates. On a boat, it's typically a 12V DC battery bank (or 24V/48V on larger vessels), but can also include shore power (AC), generators, or solar panels.

- Protection Devices: Fuses and circuit breakers are non-negotiable. They protect your wiring, equipment, and vessel from overcurrents that could lead to overheating or fire. A fuse sacrifices itself; a breaker can be reset.

- Control Devices: Switches are the most common control device, allowing you to turn circuits on and off. Relays are another form of control, using a small current to switch a larger current, often found in high-draw applications.

- Loads: These are the devices that use the electricity to perform a function. Lights, pumps, stereos, electronics, chargers – anything that consumes power is a load.

- Conductors: The wires themselves, which carry the electricity between components. Proper wire sizing is paramount to prevent voltage drop and overheating.

Understanding these basic symbols and components is your first step toward confidently interpreting any vessel wiring schematic.

The Backbone: Power Distribution and Protection

Every electrical system on your boat begins and ends with power management. It's the critical foundation that ensures reliable, safe operation of all your systems.

Batteries and Battery Switches: Your Vessel's Heartbeat

Your battery bank is the heart of your DC electrical system. Marine batteries are designed to provide sustained power for various loads. But managing this power effectively is key.

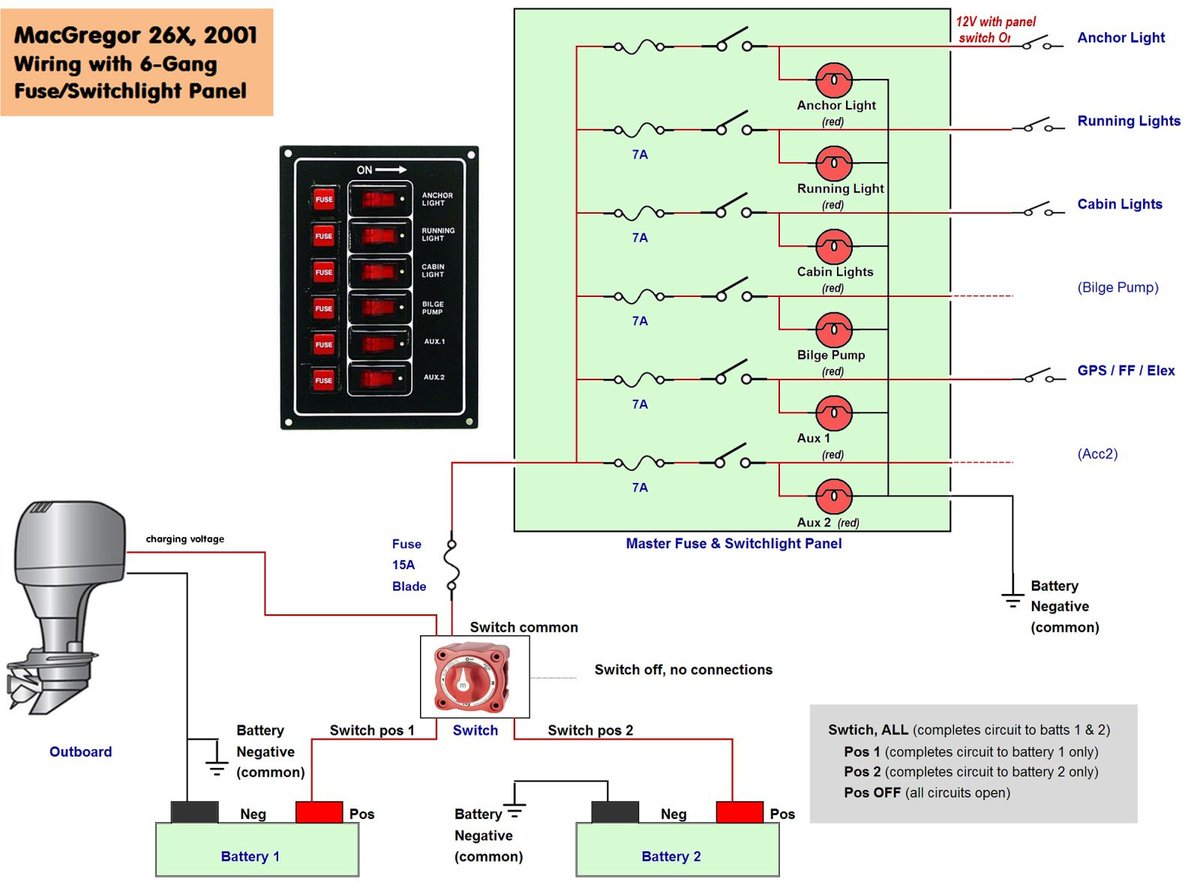

- Battery Switches: These are more than just on/off switches; they're safety devices and power management tools. A typical setup might include:

- OFF: Disconnects all batteries from the system.

- BATTERY 1: Connects only battery 1 to the load.

- BATTERY 2: Connects only battery 2 to the load.

- BOTH/COMBINE: Connects both batteries in parallel to provide maximum cranking power or combine charging.

Always consult your boat's specific schematic to understand how your battery switches are configured.

Fuse Panels and Circuit Breakers: The Guardians of Your Wires

These are your system's essential protective layers, preventing overcurrents from damaging equipment or, worse, causing fires.

- Fuses: These are single-use devices that contain a metal strip designed to melt and break the circuit if the current exceeds a certain amperage. They're common for individual components or smaller circuits.

- Circuit Breakers: These are resettable switches that automatically trip (open the circuit) when an overcurrent occurs. Once the fault is cleared, they can be reset, making them convenient for frequently used circuits or where a tripped fuse would be problematic (e.g., bilge pump).

Marine electrical systems often use a combination: a main circuit breaker for the entire DC panel, and then individual fuses or smaller breakers for each accessory circuit. Always ensure the fuse or breaker is correctly sized for the wire gauge and the maximum anticipated load of the circuit it protects. Over-fusing is incredibly dangerous.

Grounding Systems: Critical for Safety and Function

The "ground" on a DC system is actually the negative return path to the battery. A robust, properly installed grounding system is non-negotiable for both safety and optimal performance.

- Common Ground Bus: Most marine electrical systems utilize a common grounding bus bar, to which all negative wires from various loads (lights, pumps, electronics) are connected. This bus bar is then connected with a heavy gauge wire back to the battery's negative terminal.

- Importance of Good Grounds:

- Safety: A poor ground can lead to stray currents, which cause galvanic corrosion (eating away at underwater metals). More critically, it can prevent safety devices from working correctly.

- Functionality: Many electronics are highly sensitive to voltage drops and noise caused by inadequate grounding, leading to erratic behavior or poor performance.

- Corrosion Prevention: A well-designed grounding system minimizes potential differences that drive corrosion.

Never underestimate the importance of clean, tight, and robust ground connections. They are just as vital as the positive connections in any circuit.

Illuminating the Path: Navigation Light Wiring Schematics

Navigation lights are not mere adornments; they are critical safety equipment dictated by international regulations (COLREGs – International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea). Understanding their wiring is paramount.

IMO/COLREGs Requirements: More Than Just Bright Lights

Different types of vessels and varying lengths require specific navigation light configurations. The core goal is to indicate your vessel's size, direction of travel, and status (e.g., at anchor, under sail, underway).

- Port Light: Red, visible over an arc of 112.5 degrees, from dead ahead to 22.5 degrees abaft the beam on the port (left) side.

- Starboard Light: Green, visible over an arc of 112.5 degrees, from dead ahead to 22.5 degrees abaft the beam on the starboard (right) side.

- Stern Light: White, visible over an arc of 135 degrees, centered aft.

- Masthead Light: White, visible over an arc of 225 degrees, from dead ahead to 22.5 degrees abaft the beam on both sides. Required for power-driven vessels.

- All-Around Light: White, visible over 360 degrees. Often used as an anchor light or combined with a masthead light on smaller powerboats.

Common Wiring Setups for Different Vessel Types

- Powerboats Under 12m (39.4 ft): Often use a combination masthead/all-around light forward, and separate stern light. Or, separate port/starboard lights and an all-around masthead light (which doubles as an anchor light). The schematic will show switches to activate these lights independently or in combination, depending on whether the vessel is underway or at anchor.

- Sailboats Underway: Typically use separate port, starboard, and stern lights. A masthead light may be used in conjunction with these, or a tricolor light (combining port, starboard, and stern in one unit at the masthead) can be used when sailing. When at anchor, an all-around white anchor light is used.

- Larger Vessels: May have more complex systems, including multiple masthead lights, towing lights, and specialized working lights, all controlled from a central panel with individual circuits.

Troubleshooting Common Navigation Light Issues

If your nav lights aren't working, a wiring diagram is your best friend. Here's a typical troubleshooting path:

- Check the Switch: Ensure it's in the "on" position and receiving power.

- Inspect the Bulb/LED: Is it burnt out? Replace it.

- Examine the Fuse/Breaker: Is it blown or tripped? Replace the fuse or reset the breaker after identifying and fixing the cause of the overcurrent.

- Verify Connections: Check for loose or corroded wires at the light fixture, switch, and fuse panel. Corrosion is a common culprit in the marine environment.

- Test for Power/Ground: Use a multimeter to confirm power at the light fixture's positive terminal and a solid ground connection at its negative terminal. No power? Work backward along the schematic to the switch, then the fuse, then the battery.

Remember, marine environments are harsh. Wiring, connections, and fixtures are constantly exposed to moisture, salt, and vibration, making regular inspection crucial.

Beyond the Beacons: General Lighting and Accessory Wiring

While navigation lights keep you safe at night, other lighting and accessories make your time on the water comfortable, productive, and fun. Each requires proper wiring to function reliably and safely.

Interior Lighting: Cabin and Courtesy Lights

From overhead cabin lights to subtle courtesy lights guiding steps in the dark, these systems generally involve straightforward circuits: a power source, a fuse/breaker, a switch, and the light fixture itself.

- Considerations:

- LED Upgrades: Many boat owners upgrade to LED lighting for lower power consumption, longer life, and less heat generation. Ensure any replacement LEDs are marine-grade.

- Dimmer Switches: Can add comfort and adjustability to cabin lighting.

- Waterproofing: Especially for head compartments or galley areas, ensure fixtures are rated for damp environments.

Deck and Spreader Lights

These lights are crucial for nighttime tasks, docking, or illuminating the deck. They are exposed to the elements, so their wiring demands extra attention.

- Wiring Challenges: Longer wire runs from the main panel to the mast (for spreader lights) or bow (for deck lights) mean increased potential for voltage drop. Proper wire gauge selection is critical here.

- Water ingress: Ensure all connections at the fixture and along the wire run are properly sealed and protected from water. Heat-shrink tubing with adhesive is your friend.

Accessory Circuits: Pumps, Electronics, and Chargers

This is where the complexity can really begin to snowball. Modern vessels are packed with electronics, pumps, and other accessories, each needing its own dedicated circuit.

- Bilge Pumps: Absolutely non-negotiable. Bilge pump wiring often includes a float switch for automatic operation and a manual override switch at the helm. It's crucial this circuit is robust, adequately protected, and accessible.

- Marine Electronics: GPS/chartplotters, fish finders, radar, VHF radios – these require stable, clean power. Many electronics are sensitive to voltage fluctuations.

- Dedicated Circuits: High-value electronics often benefit from dedicated circuits to minimize interference and ensure consistent power.

- Filtering: Sometimes noise filters are needed to prevent electrical interference from other devices.

- Charging Systems: Shore power chargers, DC-DC chargers, and solar charge controllers all have specific wiring requirements, often involving heavy gauge wiring and robust fusing.

- Entertainment Systems: Stereos, TVs, and USB charging ports add convenience but require careful power planning.

Considerations for High-Draw Accessories

Devices like electric windlasses, thrusters, inverters, or large audio amplifiers draw significant current.

- Heavy Gauge Wire: Absolutely essential to prevent voltage drop and overheating.

- Dedicated Breakers/Fuses: Often directly connected to the battery bank (via a large main fuse/breaker) due to their high current demands, bypassing the main accessory panel.

- Relays: May be used to control high-current devices with a smaller switch at the helm.

For those working with specific vessel models, having access to detailed NauticStar 205 DC wiring diagrams can be a game-changer for maintenance and upgrades, providing a precise map of every circuit.

The Journey from Diagram to Deck: Installation Best Practices

Reading a schematic is one thing; translating it into a functional, safe electrical system on your boat is another. Here's how to bridge that gap with best practices.

Planning Your Layout: Wire Runs and Component Placement

Before you cut a single wire, plan your attack.

- Minimize Wire Runs: Shorter wire runs reduce voltage drop and material cost.

- Protect Wires: Route wires through conduits, chases, or secured bundles away from sharp edges, heat sources (like engines or exhaust), and areas prone to chafing or crushing.

- Accessibility: Place components like fuse blocks, battery switches, and junction boxes in easily accessible locations for maintenance and troubleshooting.

- Water Protection: Keep all connections and sensitive components as dry as possible. Avoid routing wires low in the bilge if alternatives exist.

Wire Selection: Gauge, Type, and Insulation

This is not the place to cut corners. Marine wire is different from automotive or household wire for a reason.

- Gauge (AWG): Always match wire gauge to the circuit's expected current draw and the length of the run (positive and negative return path). Consult AWG marine ampacity charts; they factor in temperature and bundling. Under-gauged wire is a fire hazard.

- Type (Stranded vs. Solid): Marine wiring must be stranded. Solid wire fatigues and breaks with vibration.

- Insulation: Use tinned copper wire with heavy-duty, marine-grade insulation (e.g., PVC or cross-linked polyethylene – XLPE). Tinned copper resists corrosion, which is critical in a saltwater environment.

Crimping, Soldering, and Connections: The Lifeline of Reliability

Poor connections are the source of most marine electrical problems.

- Crimping (Preferred): Use only high-quality, heat-shrink crimp connectors (tinned copper) and the correct crimping tool (ratcheting type). A good crimp is strong, weather-resistant, and provides excellent electrical contact. Always use heat shrink tubing with internal adhesive to seal crimps against moisture and corrosion.

- Soldering (Secondary): While soldering provides a strong electrical connection, it can make the wire brittle at the solder joint, prone to breaking under vibration. If you must solder, ensure it's well-supported and sealed. Never solder connections that are under strain.

- Terminal Blocks/Bus Bars: Use marine-grade terminal blocks and bus bars to consolidate connections neatly and safely. Ensure they have covers to prevent accidental contact.

- Dielectric Grease: Apply to terminal posts and non-crimp connections to prevent corrosion.

Labeling and Documentation: Your Future Self Will Thank You

A beautifully wired boat that isn't labeled is a nightmare to troubleshoot.

- Label Every Wire: Use marine-grade, indelible labels at both ends of every wire, identifying its function (e.g., "Bilge Pump," "Port Nav Light").

- Update Your Schematics: Any time you make a change, immediately update your vessel's wiring diagram. Keep both a physical and digital copy. This creates an invaluable historical record.

Testing Your Work: Trust, But Verify

Never assume a circuit is correct until you've tested it.

- Visual Inspection: Before applying power, double-check all connections.

- Continuity Test: Use a multimeter to ensure proper continuity and check for any accidental shorts to ground.

- Functionality Test: Power up the circuit and test the component. Check for correct voltage and current draw (if possible).

- Load Test: For critical circuits (like bilge pumps), verify they can handle their intended load.

Common Wiring Pitfalls to Avoid

Even experienced DIYers can fall into these traps. Being aware of them can save you headaches, and potentially, your boat.

- Under-gauged Wires: The most common and dangerous mistake. Too small a wire for the current and length of run leads to excessive voltage drop, overheating, and fire risk. Always consult a marine wire gauge chart.

- Poor Connections: Loose, corroded, or improperly crimped connections create resistance, leading to heat, voltage drop, and intermittent operation. The marine environment is particularly unforgiving.

- Inadequate Fusing/Protection: Using the wrong size fuse or circuit breaker, or worse, bypassing them, leaves your wiring and equipment vulnerable to overcurrents. Never "fix" a repeatedly blown fuse by installing a larger one without finding the root cause.

- Ignoring Grounding: A weak or corroded ground connection is just as bad as a poor positive connection. It can lead to erratic behavior in electronics, promote galvanic corrosion, and pose safety risks.

- Lack of Weatherproofing: Exposed connections, non-marine-grade components, and unsealed wire runs are an open invitation for moisture and corrosion to wreak havoc. Every marine connection should be watertight where exposed.

- Overloading Circuits: Adding too many accessories to an existing circuit can cause the fuse or breaker to trip constantly, or lead to dangerous overheating if the protection isn't adequate. Always consider the total load.

- Disorganized Wiring: A tangled mess of unlabeled wires is a nightmare for troubleshooting and maintenance. Take the time to route, bundle, and label neatly.

Maintaining Your Vessel's Nervous System

Like any critical system on your boat, your electrical wiring isn't a "set it and forget it" component. Regular care extends its life and ensures reliable operation.

- Regular Inspections: Periodically open up electrical panels, examine battery terminals, and check connections. Look for signs of corrosion (green or white powdery deposits), frayed insulation, or melted plastic. Pay special attention to areas exposed to the elements or high vibration.

- Cleaning Connections: Disconnect power and clean corroded terminals with a wire brush or baking soda solution. Reapply dielectric grease to battery terminals and non-crimp connections after cleaning.

- Updating Schematics After Modifications: Every time you add, remove, or change an electrical component, make sure your diagrams are updated. This keeps your "map" current and accurate for future troubleshooting.

- Tighten Terminals: Vibration can loosen screw terminals over time. Gently snug them up, but avoid overtightening, which can strip threads or crack housings.

A proactive approach to electrical maintenance ensures your boat's systems remain robust and dependable, giving you one less thing to worry about when you're out on the water.

Your Questions, Answered: Wiring FAQs

We've covered a lot of ground, but here are some quick answers to common questions about vessel wiring.

Can I mix AC and DC wiring?

No, definitely not in the same conduit or on the same terminal block. AC (shore power/generator) and DC (battery) systems must be kept entirely separate due to different safety standards, voltage levels, and grounding requirements. Combining them can lead to dangerous situations and system failures.

How do I find a short circuit?

A short circuit causes a fuse to blow or a breaker to trip. To find it, disconnect all loads from the circuit. Then, systematically reconnect one load at a time, checking the fuse/breaker, until the fault reappears. Alternatively, use a multimeter to check for continuity between the positive wire and ground (or between positive and negative after the load) with the power off. A short will show very low resistance.

What's the difference between a fuse and a circuit breaker?

Both protect circuits from overcurrent. A fuse is a one-time device that melts and breaks the circuit, requiring replacement. A circuit breaker is a resettable switch that trips open when an overcurrent occurs and can be reset once the fault is cleared. Breakers are more convenient for frequently used circuits.

How often should I check my wiring?

A thorough inspection should be part of your annual pre-season maintenance. However, quickly check critical systems (like bilge pump wiring) more frequently, especially after heavy use or exposure to harsh weather.

Why do my lights flicker?

Flickering lights often indicate a loose or corroded connection somewhere in the circuit, an intermittent short, or a voltage drop caused by undersized wiring or an inadequate power supply (e.g., a failing battery or alternator). Start by checking connections at the light, switch, and fuse panel.

Empowering Your Next Nautical Project

Understanding Navigation, Lighting, and Accessory Wiring Schematics is more than just a technical skill; it's a foundational element of safe and enjoyable boating. Whether you're troubleshooting an annoying flicker, installing new electronics, or simply performing routine maintenance, a clear understanding of your vessel's electrical nervous system empowers you to tackle tasks with confidence and precision.

By embracing these principles, you're not just ensuring your lights turn on or your pump runs; you're investing in the reliability, safety, and longevity of your vessel. So, grab your multimeter, unroll those schematics, and approach your next electrical project with the knowledge that you're well-equipped to keep your boat running smoothly and safely on the water.