Building a ship is an intricate dance of engineering, materials science, and meticulous planning. Like assembling a giant, complex puzzle, every piece—from the mighty keel to the smallest scupper—must fit precisely and perform its duty flawlessly. For anyone involved in shipbuilding, maintenance, or marine engineering, understanding the foundational structure of a vessel is paramount. This is where Hull & Deck Component Exploded Views and Assembly Guides become indispensable, offering a crystal-clear roadmap to the ship's skeleton, muscles, and skin. These critical documents translate abstract design into tangible realities, revealing how every plate, beam, and frame comes together to form a robust, seaworthy vessel.

At a Glance: Deciphering Ship Anatomy

- Longitudinal vs. Transverse: Ships rely on two primary types of structural members. Longitudinal components (like the keel and deck girders) run the length of the ship, tackling bending stresses from waves. Transverse components (such as frames and deck beams) run across, primarily resisting water pressure and providing shape.

- The Skin of the Ship: Plating forms the outer hull and decks, contributing significantly to strength and sealing the vessel. Knowing about strakes, seams, and butts is key to understanding how these panels are joined.

- Framing Systems Define a Ship's Core: Whether a vessel uses transverse, longitudinal, or a combination framing system dictates its structural integrity, cargo capacity, and suitability for different missions. Longer ships often favor longitudinal framing for better resistance to hogging and sagging.

- Double Bottom for Safety & Utility: An inner bottom creates a watertight double hull, enhancing safety against grounding and providing valuable space for fuel, water, or ballast.

- Navigating Openings: Any break in the hull or deck, from a hatchway to a porthole, is a structural vulnerability. Proper design, reinforcement, and rounded corners are crucial to maintain strength and prevent cracking.

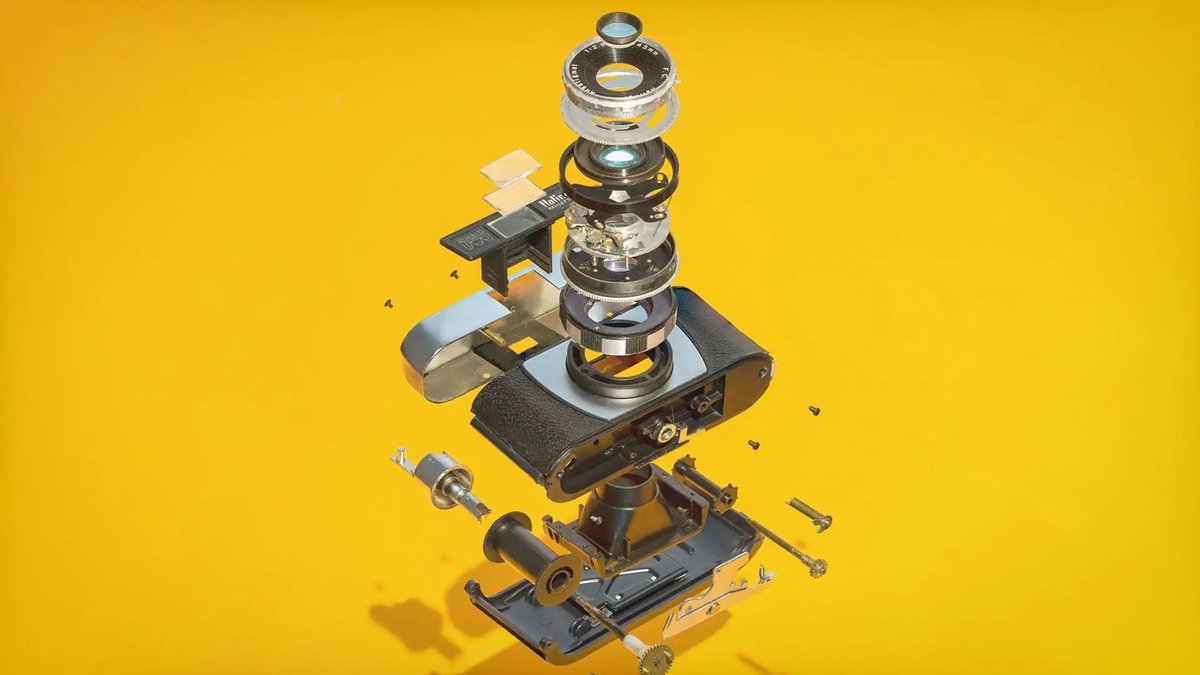

- Assembly Guides as Your Blueprint: These guides, often presented as exploded views, demystify complex assemblies, showing individual components and their precise arrangement, aiding in construction, repair, and modification.

The Blueprint of a Ship: Understanding Exploded Views

Imagine a complex machine, taken apart and laid out, each component numbered and labeled, with arrows showing how they connect. That's essentially an exploded view, a powerful visual tool in engineering. For a ship, these views peel back the layers of steel and reveal the intricate network of girders, frames, and plates that give a vessel its strength and shape.

These comprehensive assembly guides aren't just for builders; they're vital for surveyors assessing structural integrity, for repair crews needing to replace a damaged section, and even for owners looking to understand their vessel's resilience. They move beyond simple line drawings, offering a three-dimensional understanding of how a ship's components interlock, brace, and support each other against the relentless forces of the sea.

The Backbone and Ribs: Longitudinal & Transverse Structural Components

A ship's structural integrity hinges on a finely balanced interplay between members running lengthwise and those running across its width. Think of a ship's structure like a skeleton: you have a spine and ribs, each playing a distinct, vital role.

Longitudinal Structural Components: The Ship's Spine

These members primarily resist the powerful forces of longitudinal bending stress, which causes a ship to "hog" (bend upwards in the middle) or "sag" (bend downwards in the middle) when encountering waves.

- Keel: This is the absolute cornerstone, a large center-plane girder running along the entire length of the ship's bottom. It's the vessel's primary longitudinal strength member, often likened to the spine of a mammal. Without a strong keel, the ship would literally break its back under stress.

- Longitudinals: Running parallel to the keel along the bottom and sometimes the sides and decks, these girders provide crucial additional longitudinal strength. They distribute stress along the hull, preventing local buckling and contributing to overall stiffness.

- Deck Girders: Found within the deck frame, these are longitudinal members designed to support the deck plating and transfer loads to the ship's main structure. They ensure the deck can withstand heavy weights and remain flat.

- Stringers: Typically smaller than main longitudinals, stringers run along the sides of the ship. They offer localized longitudinal strength and stiffness, especially important in resisting lateral hydrostatic pressure and maintaining the hull's shape.

Transverse Structural Components: The Ship's Rib Cage

These components primarily resist hydrostatic loads—the immense pressure exerted by water on the ship's hull—and help the ship maintain its cross-sectional shape, preventing distortion or "racking."

- Floor: These are deep frames that run from the keel out to the "turn of the bilge," the curved section where the bottom meets the side. Floors are critical in the lower part of the ship, resisting upward water pressure and forming the structure for the double bottom.

- Frame: Running from the keel (or connected to floors) up to the deck, frames are the ship's ribs. They provide continuous support to the shell plating, resisting hydrostatic pressure, wave impacts, and external forces. Their spacing and depth are crucial design considerations based on the ship's size and intended service.

- Deck Beams: These are the transverse members within the deck frame. They support the deck plating, transfer deck loads to the frames and girders, and help maintain the ship's transverse shape at each deck level.

The Skin of the Ship: Plating and Its Significance

While the internal members provide the skeleton, the plating is the skin that closes in the top, bottom, and sides of the structure. It’s not just for keeping water out; plating is a fundamental contributor to the ship's longitudinal strength and directly resists hydrostatic pressure and potential side impacts.

Naval architects meticulously choose plate thickness and material, weighing strength requirements against the trade-offs of increased cost, reduced interior space, and limits on mission equipment.

Shell Plating Details: A Closer Look at the Hull's Surface

Understanding the terminology of plating is essential for anyone reviewing Hull & Deck Component Exploded Views and Assembly Guides:

- Strakes: These are the rows of plating that run longitudinally along the ship's hull.

- Seams: Horizontal welded joints connecting adjacent strakes.

- Butts: Vertical welded joints connecting individual plates within a single strake.

- Drop Strakes: Plates that do not extend the entire length of the ship.

- Through Strakes: Plates that run continuously from the bow (stem) to the stern.

- Stealer Plate: An oversized plate used to smoothly merge a drop strake into a through strake, especially at the ship's ends where lines converge.

- Sheer Strake: Located at the deck edge, this is typically heavier and thicker than the regular side shell plating. It's a critical stress point, particularly vulnerable to cracking under hogging and sagging. For this reason, its upper edges are often ground smooth, and unnecessary welding onto it is avoided.

- Keel Plates (Keel Strake): These are the plates that form the central keel strake at the very bottom of the ship.

- A-Strakes / Garboard Strakes: The strakes immediately outboard of the keel plates.

Openings: Necessary Evils and Their Reinforcement

Any opening in the shell plating, whether a porthole, a watertight door, or a large cargo hatch, represents a structural discontinuity and a potential weak point. Proper design and reinforcement are critical to prevent cracks and maintain the hull's integrity.

- Rounded Corners are Non-Negotiable: Square corners concentrate stress, making them highly susceptible to cracking. Therefore, all openings in the shell plating must have rounded corners. Large openings, such as cargo doors, are particularly vulnerable and require robust reinforcement with face bars, web frames, and insert plates.

- Hatchway Details: Hatch coamings (the raised edges around hatches) have specific height requirements: 600 mm on the freeboard deck and 450 mm on exposed superstructure decks (aft of ¼ of the ship's length from the stem). Again, squared corners are strictly forbidden. The radius at corners must be at least 1/24th of the opening breadth, but never less than 300mm. Critically, doubling plates are not permitted in welded decks for reinforcement; instead, insert plates must be precisely fitted at hatch corners to distribute stress effectively.

- Suction and Discharge Fittings: These essential openings for systems like bilges or sewage also require careful attention. Discharges below the freeboard deck typically need non-return valves (though engine room discharges are often exempted). Scuppers (drains) passing through the shell plating below 450 mm of the freeboard deck or less than 600 mm above the load waterline must have an automatic non-return valve fitted at the shell. Scuppers from a deck below the freeboard deck must either drain to the bilges or be fitted with a self-closing and non-return (SDNR) valve.

How Ships Hold Together: Framing Systems Explained

The choice of framing system is a fundamental design decision that profoundly impacts a ship's strength, cargo capacity, and construction cost. Hull & Deck Component Exploded Views and Assembly Guides will clearly depict which system, or combination, is employed.

1. Transverse Framing System

- Purpose: Primarily designed to stiffen the shell plating, prevent buckling from hydrostatic pressure, resist distortion (racking), and support the ends of deck beams. It excels at providing transverse strength.

- Characteristics: Frames are closely spaced and continuous from the bottom to the deck. Longitudinal members, conversely, are widely spaced but deep.

- Components: Relies heavily on frames, floors, deck beams, and plating.

- Application: Most commonly found in ships shorter than 300 feet (about 90 meters) and submersibles, where longitudinal bending stresses are less pronounced.

- Structure: Deck beams effectively tie the upper ends of the frames together. Fewer, deeper, widely spaced longitudinals support the inner bottom and provide the necessary longitudinal strength. Those longitudinals supporting decks are specifically called Girders. Transverse bulkheads—watertight barriers that divide the ship into compartments—play a significant role, contributing substantially to transverse strength and offering vertical support for decks.

- Advantages: Creates open, nearly rectangular interior spaces. This makes it ideal for stowing large, irregular items or vehicles, making it a popular choice for Roll-on/Roll-off (Ro-Ro) vessels.

- Disadvantages: Typically requires more closely spaced transverse bulkheads or additional pillars/stanchions to adequately support the decks, which can segment cargo spaces.

2. Longitudinal Framing System

- Purpose: Primarily designed to provide robust longitudinal strength, crucial for resisting hogging and sagging stresses.

- Characteristics: Longitudinals (like stringers on the sides) are spaced frequently but are shallower than in a transverse system. Frames, on the other hand, are widely spaced and require support from heavy, vertical web frames, typically fitted about every 4 meters.

- Application: Preferred for ships longer than 300 feet, which experience considerable longitudinal bending stress due to their length.

- Structure: Often incorporates an inner bottom, which provides additional longitudinal and transverse strength. Girders are strategically placed in high-stress areas, such as within the double bottom and directly under the main deck.

- Advantages: Allows for widely spaced transverse bulkheads, creating large, continuous cargo spaces. This is ideal for liquid cargoes (e.g., oil tankers) as it reduces "free surface effects" (the sloshing of liquids, which can destabilize a vessel). This system is also better equipped to resist buckling when the hull is under hogging stress.

- Disadvantages: The frequent, shallow longitudinals reduce the overall internal volume and can make loading or unloading break-bulk items or large, irregular items more challenging, as there are no large, open interior spaces.

3. Combination Framing System

- Purpose: Developed to overcome the disadvantages of the purely longitudinal system in dry cargo ships and to optimize the structural arrangement for cost-effectiveness and efficiency. Most modern ships utilize some form of this system.

- Characteristics: It strategically combines both systems. Longitudinal frames are used where longitudinal strength is most critical, typically at the ship's bottom and under the strength deck (the uppermost continuous deck). Transverse frames are then used on the ship’s sides, where longitudinal stresses are generally smaller but hydrostatic pressure is still significant. Heavy transverse beams and plate floors are fitted at regular intervals to provide overall transverse strength and to support the longitudinals.

- Typical Application: A common combination might involve longitudinals and stringers with relatively shallow frames, interspersed with a much deeper, heavy frame fitted every third or fourth frame space to provide significant transverse stiffness. This hybrid approach leverages the best of both worlds.

Safety and Utility Below: The Double Bottom Tank

A pivotal safety and operational feature in many modern vessels is the double bottom tank. This design element is clearly depicted in comprehensive Hull & Deck Component Exploded Views and Assembly Guides, showing its construction and integration.

- Definition: The double bottom is essentially a secondary, watertight "inner bottom" (often called the tank top) constructed above the bottom shell, extending watertight to the bilges (the lowest internal parts of the hull).

- Safety: Its primary function is safety. If the outer bottom shell is breached (e.g., due to grounding or collision), only the double bottom space may flood, providing a significant safety margin and preventing catastrophic ingress of water into the cargo holds or machinery spaces.

- Utilization: Beyond safety, the double bottom space is incredibly useful. It's often divided into compartments to store essential liquids like oil fuel, fresh water, and ballast water. These compartments can be deeper in certain areas, such as machinery spaces or at the ship's ends, to accommodate required capacities and aid in trimming the vessel.

- Construction: To avoid sudden structural discontinuities that could create stress points, any increase in double bottom height is typically implemented as a gradual taper longitudinally.

- Framing: The double bottom itself can be framed either longitudinally or transversely. For ships exceeding approximately 120 meters in length, longitudinal framing is generally preferred within the double bottom. This helps prevent buckling of both the inner bottom and the outer bottom shell under longitudinal bending stresses, a common issue with welded transverse framing in longer vessels.

- Functions: In summary, the double bottom serves multiple critical roles: it resists upward hydrostatic pressure, withstands bending stresses, protects against damage from grounding or underwater shock, and provides a smooth inner bottom surface which facilitates cargo arrangement, equipment placement, and cleaning operations. It's fundamentally a robust structure consisting of two watertight bottoms separated by a void space.

Deck Dynamics: Supporting the Upper Levels

The decks of a ship are far more than just walking surfaces; they are crucial structural elements that contribute to both longitudinal and transverse strength. Their ability to manage and distribute loads is meticulously detailed in 2006 NauticStar 205 DC schematics, offering a clear example of how deck components are organized.

Deck Plating forms the surface of each deck level. Beneath this plating lies a network of deck beams and girders, working in concert to provide stiffness. These deck structures, in turn, are supported by pillars (also known as stanchions). These vertical members run down through the ship, connecting the deck structure with the bottom structure. Their primary role is to transmit heavy deck loads (from cargo, equipment, or even personnel) directly to the ship's bottom structure, where these forces are then safely distributed into the robust floors and the keel. Without adequately designed and placed pillars, decks could sag or even collapse under load.

Mind the Gaps: Discontinuities and Openings

While essential for access, light, and functionality, any opening in a ship's hull or deck creates a discontinuity in the otherwise continuous structure. These discontinuities are potential stress concentrators and must be designed and reinforced with extreme care to maintain the vessel's overall strength and watertight integrity.

Hatchways: Gateway to Cargo

Hatchways, the large openings in decks that allow access to cargo holds, are among the most significant discontinuities. Their design is subject to strict regulations:

- Coaming Height: The raised coamings around hatchways serve to prevent water ingress. They must be at least 600 mm high on the freeboard deck and 450 mm high on exposed superstructure decks (aft of ¼ of the ship's length from the stem).

- Corner Design: Squared corners on hatchways are forbidden. Instead, openings must be elliptical, parabolic, or, most commonly, have rounded corners. The radius at these corners is crucial for stress distribution and must be at least 1/24th of the opening's breadth, but never less than 300mm. This larger radius helps to spread out the stress, significantly reducing the likelihood of fatigue cracks developing.

- Reinforcement: To compensate for the material removed by the opening, hatchways require robust reinforcement. Importantly, doubling plates (an extra plate welded over the original) are not permitted in welded decks as they can create new stress concentrations. Instead, insert plates must be precisely fitted at hatch corners. These are thicker, specially shaped plates welded flush into the deck, ensuring a smooth transition and effective stress transfer.

Openings in the Shell: Suction and Discharge Fittings

Even smaller openings in the shell plating, such as those for suctions, discharges, or scuppers, are meticulously regulated to prevent water ingress:

- Discharges Below Freeboard Deck: Any discharge outlet located below the ship's freeboard deck (the uppermost continuous deck exposed to the weather) must be fitted with non-return valves to prevent water from flowing back into the ship. A common exception is discharges originating from continuously manned engine rooms, where constant supervision is expected.

- Critical Scupper Placement: Scuppers (deck drains) that pass through the shell plating in vulnerable locations – specifically, more than 450 mm below the freeboard deck or less than 600 mm above the load waterline – must be equipped with an automatic non-return valve fitted directly at the shell. This ensures that even if the scupper line is damaged, water cannot freely enter the hull.

- Scuppers from Below Decks: Scuppers draining from a deck that is below the freeboard deck must either be routed downwards to the ship's bilges for collection and pumping, or they must be fitted with a self-closing and non-return (SDNR) valve to prevent backflow and uncontrolled flooding.

Bringing It All Together: The Assembly Process and Beyond

Understanding Hull & Deck Component Exploded Views and Assembly Guides isn't just an academic exercise; it's a practical necessity that underpins the entire lifecycle of a vessel. From the initial cuts of steel to a ship's final decommissioning, these documents serve as the authoritative reference.

For shipyards, these guides are the instruction manuals for fabrication and erection, ensuring that sections are pre-fabricated correctly and then precisely joined on the slipway or in the dry dock. For marine engineers and naval architects, they are tools for analysis, allowing them to simulate stresses, plan modifications, or troubleshoot structural issues. For operations and maintenance teams, they provide crucial insight into the location of critical members, access points, and potential vulnerabilities during repairs or routine inspections.

The complexity of modern shipbuilding, with its advanced materials and sophisticated designs, only amplifies the importance of these comprehensive guides. They ensure consistency, enforce safety standards, and ultimately contribute to the creation of vessels that are not only efficient but also resilient and trustworthy in the challenging marine environment.

Common Questions About Ship Construction

Why are there different framing systems?

Ships encounter different types of stress depending on their size and intended use. Shorter ships (under ~300 ft) are more susceptible to hydrostatic pressure loads across their width, making transverse framing ideal for maintaining cross-sectional shape and providing open cargo spaces. Longer ships, however, face significant longitudinal bending stresses (hogging and sagging) from waves. Longitudinal framing better resists these forces. The combination system then seeks to optimize, using longitudinals where bending stress is highest (bottom, main deck) and transverse frames elsewhere, balancing strength, cost, and cargo space utility.

What's the most critical part of the hull structure?

While every component plays a role, the keel is arguably the most critical. It's the ship's backbone, providing the primary longitudinal strength. Damage to the keel can severely compromise the entire vessel's structural integrity, making it highly vulnerable to breaking apart under bending stresses. Closely following in importance are the sheer strake and the bilge area, as these are also zones of high stress concentration and are particularly prone to cracking under hogging and sagging.

Why are rounded corners important for openings?

Rounded corners are essential because they prevent stress concentration. When there's a sharp corner (like in a square opening), forces flowing through the material converge at that point, creating an area of extremely high stress. This makes the material much more likely to crack, especially under repeated loading and unloading (fatigue) or dynamic stresses at sea. A rounded corner allows these forces to flow more smoothly around the opening, distributing the stress over a larger area and significantly reducing the risk of structural failure.

Building Confidence, One Component at a Time

The world of shipbuilding is one of immense forces and meticulous design. Hull & Deck Component Exploded Views and Assembly Guides are more than just technical drawings; they are the Rosetta Stone for understanding how these monumental structures withstand the elements. For anyone from a shipyard engineer to a vessel owner, mastering these guides means gaining a profound appreciation for a ship's integrity and the foundational principles that keep it afloat and safe. By delving into these comprehensive resources, you're not just learning about steel and welds; you're gaining the insight and confidence needed to ensure a vessel's enduring seaworthiness.